Unfinished Tales: The Essential Tolkien Collection Readers Might Want To Check Out Before The Silmarillion

For readers who finish The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit hungry for more Middle-earth, the natural instinct is to reach for The Silmarillion. That instinct, while understandable, often leads to frustration.

The Silmarillion reads like the Old Testament with genealogies, historical chronicles, descriptions of land masses and migrations, names that shift between languages, and a narrative structure that prioritizes mythological scope without character arcs. It’s Tolkien’s creation myth, his First Age history, and the foundation upon which everything else is built. It’s also dense, challenging, and deliberately archaic in style.

For the average Lord of the Rings fan looking for more stories rather than more mythology, there’s a better entry point: Unfinished Tales of Númenor and Middle-earth.

What Christopher Tolkien Assembled

After J.R.R. Tolkien’s death in 1973, his son Christopher inherited a vast archive of manuscripts, notes, and fragmentary narratives. While working on The Silmarillion, Christopher realized there was substantial material that didn’t fit into that single-volume synthesis but would interest readers who already knew The Lord of the Rings.

Rather than forcing these pieces into a coherent whole, Christopher published them as they were: unfinished, fragmentary, sometimes contradictory, but narratively compelling. Unfinished Tales (1980) is explicitly a collection, not a unified work, and Christopher treated each piece according to how far his father had taken it.

Some texts he left almost untouched. Others he stitched together from multiple drafts, always noting where the narrative breaks off or where versions conflict. Crucially, unlike The Silmarillion, he did not try to enforce strict consistency with the published works. He preserved contradictions and alternative conceptions, adding extensive editorial notes explaining variants, dating, and how each piece fits—or fails to fit—into the wider legendarium.

The result is a book that feels more like archaeology than literature. You’re reading Tolkien’s drafts, his explorations, his alternative versions. But because these are narrative fragments rather than mythological chronicles, they’re often more immediately engaging than The Silmarillion‘s grand historical sweep.

The Structure

Unfinished Tales is divided into four sections covering the First, Second, and Third Ages, plus appendices on the Istari (the wizards) and the palantíri (the seeing-stones).

The First Age material will be challenging without having read The Silmarillion first. These are stories of Túrin Turambar and Tuor, characters whose tragedies are rooted in the broader mythology of the Elder Days. They’re powerful narratives, but they assume knowledge of the Silmarils, the fall of Gondolin, and the curse of Morgoth.

The Second and Third Age material, however, is where Unfinished Tales becomes essential reading for Lord of the Rings fans.

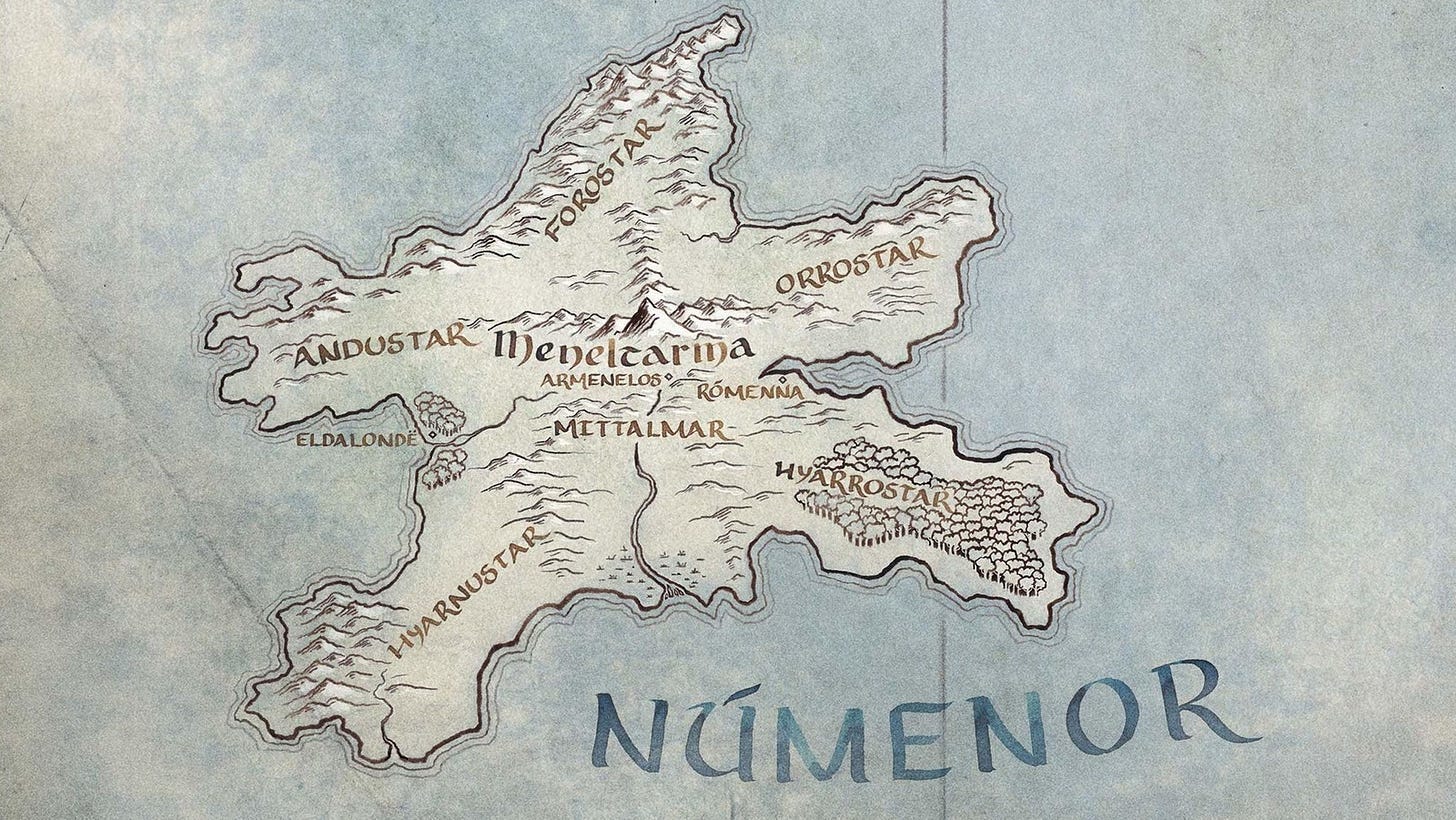

The Tale of Aldarion and Erendis

The longest Second Age narrative is “Aldarion and Erendis: The Mariner’s Wife,” a story set in Númenor during the height of its power. This is one of Tolkien’s most mature and psychologically complex works—a domestic tragedy about a marriage destroyed by conflicting priorities.

Aldarion is a mariner obsessed with the sea and with Middle-earth, constantly leaving Númenor for years at a time. Erendis is his wife, who grows to resent his absences and the sea itself. Their daughter Ancalimë becomes caught between them, shaped by her mother’s bitterness into someone who will never trust men.

There’s no magic here, no battles, no dark lords. It’s a story about two people who love each other but cannot reconcile their fundamental natures. Aldarion’s voyages are preparing Númenor for the coming conflict with Sauron, but Erendis doesn’t care about grand historical purposes—she cares that her husband is never home.

The story is unfinished. It breaks off before the resolution. But what exists is some of Tolkien’s finest character work, and it adds enormous depth to the history of Númenor that appears in The Silmarillion‘s “Akallabêth.”

The History of Galadriel and Celeborn

This section is exactly what it sounds like: a detailed (and contradictory) account of Galadriel’s history, her reasons for remaining in Middle-earth, her relationship with Celeborn, and the founding of Lothlórien.

For readers who only know Galadriel from The Lord of the Rings, this material is revelatory. She’s not just a powerful elf-lady living in a forest, but she’s one of the Noldor who rebelled against the Valar in the First Age, who came to Middle-earth in pursuit of the Silmarils, who was banned from returning to Valinor for thousands of years because of that rebellion.

Her test with Frodo’s offer of the Ring isn’t just about resisting power—it’s about finally earning the right to go home after millennia of exile. The weight of that moment in The Fellowship of the Ring increases exponentially when you understand what she’s been denied and what she’s finally being offered.

Christopher Tolkien notes that his father never settled on a single version of Galadriel’s story. The contradictions remain in the text, with editorial commentary explaining the alternatives. For some readers, this is frustrating. For others, it’s fascinating—a glimpse into Tolkien’s creative process and his constant revision of his mythology.

Gandalf and the Dwarves

The Third Age section includes “The Quest of Erebor,” which recounts how Gandalf orchestrated the events of The Hobbit from his perspective. This is essential reading for anyone who wants to understand why Gandalf chose Bilbo, why he pushed Thorin to reclaim Erebor, and how the quest to kill Smaug was actually part of a larger strategy to prevent Sauron from using the dragon in the coming war.

Gandalf explains that he feared Sauron would ally with Smaug, giving the Enemy control of the North. The quest wasn’t just about helping dwarves reclaim their homeland—it was about removing a strategic threat before the War of the Ring began.

The story also reveals Gandalf’s doubts. He wasn’t certain Bilbo was the right choice. He took a risk, and it paid off, but he didn’t know it would. This adds vulnerability to a character who often seems omniscient in The Lord of the Rings.

The Palantíri and the Istari

The appendices are some of the most valuable material in the book. “The Istari” explains who the wizards are, why they were sent to Middle-earth, and what their limitations were. Gandalf, Saruman, Radagast, and the two Blue Wizards are all Maiar. They’re presented as angelic beings sent by the Valar to oppose Sauron without using their full power.

They were forbidden from matching Sauron’s strength directly. They were meant to inspire and guide the Free Peoples, not to dominate them. Saruman’s fall is a betrayal of that mission. He sought power for himself rather than serving as a counselor.

“The Palantíri” explains the seeing-stones, how they work, who made them, and why their use is so dangerous. This adds context to Denethor’s madness and Saruman’s corruption.

The Unfinished Nature

Every piece in Unfinished Tales is incomplete in some way. Some break off mid-sentence. Others exist in multiple contradictory versions. Christopher Tolkien’s editorial notes are extensive, sometimes longer than the fragments themselves, explaining what his father intended and where the narrative was likely headed.

For readers accustomed to finished novels, this can be jarring. But it’s also part of the book’s value. You’re reading Tolkien’s workshop, seeing how he developed ideas, revised them, abandoned them, and returned to them years later.

The contradictions show Middle-earth as a living mythology in Tolkien’s mind, constantly evolving, never quite fixed. Christopher’s decision to preserve those contradictions rather than smoothing them over was the right one.

Why Read This Before The Silmarillion

The Silmarillion is essential for understanding Tolkien’s complete vision, but it’s not the best next step after The Lord of the Rings. It’s too distant, too mythological, too concerned with events thousands of years before the stories readers already care about.

Unfinished Tales bridges that gap. It gives you more Gandalf, more Galadriel, more context for The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. It explains things that were mysterious in the main narrative. It adds depth to characters you already know rather than introducing dozens of new names you’ll struggle to remember.

The First Age material will still be challenging, but the Second and Third Age sections are immediately rewarding. And once you’ve read Unfinished Tales, The Silmarillion becomes more approachable. You’ll have context for Númenor, for the Elves’ history, for why certain names and places matter.

The Quality of the Material

This is some of Tolkien’s best work. “Aldarion and Erendis” is a mature, psychologically complex story unlike anything else in the legendarium. “The Quest of Erebor” recontextualizes The Hobbit in ways that make both books richer. The material on Galadriel transforms her from a supporting character into one of the most important figures in Middle-earth’s history.

The prose is Tolkien at his finest. The fragments may be unfinished, but they’re not rough drafts. These are polished pieces that simply don’t have endings, or that exist in multiple versions because Tolkien kept revising his mythology.

Christopher’s editorial work is exemplary. His notes are informative without being intrusive, scholarly without being dry. He guides you through the contradictions and explains the context without trying to impose a single interpretation.

Final Recommendation

Unfinished Tales earns a 9/10 and stands as essential reading for anyone who loves The Lord of the Rings. It’s more immediately rewarding than The Silmarillion, more narratively focused, and more directly connected to the stories you already know.

What do you think? Should Unfinished Tales be recommended before The Silmarillion for new Tolkien readers, or is the traditional reading order still the best approach?

If you’re interested in a fun fantasy world, read The Adventures of Baron von Monocle six-book series and support Fandom Pulse!

NEXT: On Tolkien’s Abandoned Sequel “The New Shadow” And Why Middle-earth’s Fourth Age Remained Untold

I don't know, it's a tough question. I read Silmarillion before UT and the rest of the 'extra' books, and to me it was always the right choice. But then again, Simarillion is my favourite of Tolkiens' books. Also because Silmarillion was the only Tolkien's book I knew about after reading The Hobbit and LotR.

I guess it depends what the reader prefers, whether more human-sized stories with personal scale and immediacy, or a grander mythical narrative that presents Tolkien's creation myth, logic of his cosmos and tragedies spanning millenia (with a strong influence over the more personal stories). Tough choice...