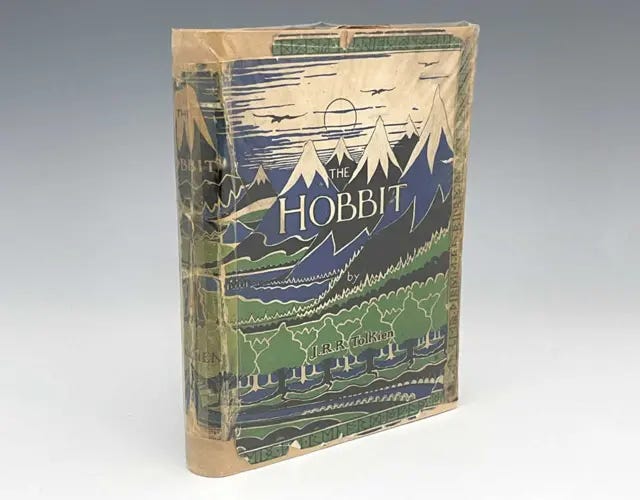

Twenty years is a long time between readings. Long enough to forget the texture of a book, the rhythm of its prose, the way it shifts and evolves as the story progresses. After working through The Silmarillion and Unfinished Tales, I returned to The Hobbit expecting a simple children’s adventure, a palate cleanser before diving back into the denser material of Middle-earth’s mythology (I’ll be reading The Book Of Lost Tales next!).

What I found instead was one of the most structurally audacious fantasy novels ever published, a book that would likely be rejected by modern editors for violating fundamental rules of narrative construction, and a story that becomes something entirely different in its final act.

The Revised Edition and Continuity

The version of The Hobbit readers encounter today is not the book Tolkien originally published in 1937. When The Lord of the Rings was in development, Tolkien realized he had a continuity problem. In the original Hobbit, Gollum willingly bets his magic ring in a riddle contest and graciously gives it to Bilbo when he loses. This didn’t align with the Ring’s corrupting nature or Gollum’s obsessive relationship with his “precious.”

In 1951, Tolkien revised the “Riddles in the Dark” chapter for the second edition. Gollum no longer offers the Ring as a prize, but instead he intends to use it to kill Bilbo after losing the contest. Bilbo escapes with the Ring by accident, and Gollum’s anguished cries of “Thief! Thief!” establish the possessive madness that defines him in The Lord of the Rings.

Tolkien handled this revision brilliantly within the fiction itself. In the prologue to The Lord of the Rings, he explains that Bilbo’s original account (the 1937 version) was a white lie, and that Bilbo had downplayed how he obtained the Ring because he was already being influenced by it. The “true” story (the revised version) only came out later when Gandalf pressed him on the details.

This meta-textual solution transformed a continuity error into characterization. The Ring was already corrupting Bilbo before he even understood what it was.

The Plot and Structure

The Hobbit follows Bilbo Baggins, a respectable hobbit who enjoys comfort and routine, as he’s recruited by Gandalf to join thirteen dwarves on a quest to reclaim their homeland of Erebor from the dragon Smaug. Bilbo is hired as a “burglar,” though he has no qualifications for the role beyond being small and quiet.

The journey takes them through the Misty Mountains, where Bilbo finds the Ring in Gollum’s cave. They’re captured by goblins (Tolkien’s term for orcs in this book), rescued by eagles, sheltered by Beorn the skin-changer, and nearly killed by giant spiders in Mirkwood. They’re imprisoned by the Elvenking (later named Thranduil, father of Legolas), escape in barrels, and finally reach the Lonely Mountain.

Bilbo enters Smaug’s lair alone, engages the dragon in conversation, and steals a cup. Smaug, enraged, attacks the nearby town of Esgaroth (Lake-town). Bard the Bowman kills the dragon with an arrow to his one vulnerable spot—information Bilbo learned during their conversation and that a thrush overheard and relayed to Bard.

The dwarves reclaim Erebor, but Thorin becomes obsessed with the treasure, particularly the Arkenstone. Armies converge: men and elves seeking compensation for Smaug’s destruction, dwarves from the Iron Hills coming to Thorin’s aid, and goblins and wargs arriving to claim the treasure for themselves. The Battle of the Five Armies erupts. Bilbo, having been knocked unconscious early in the fighting, misses most of it. Thorin is mortally wounded. The goblins are defeated. Bilbo returns home with a small portion of treasure and is largely forgotten by history.

The Protagonist Who Doesn’t Win

By modern publishing standards, The Hobbit is structurally broken. Bilbo doesn’t kill the dragon. He doesn’t fight in the climactic battle. In fact, he’s unconscious for most of it. He doesn’t recover the Arkenstone or resolve the conflict between the dwarves and the men and elves. He’s present for the major events, but he’s not the one who resolves them.

A contemporary editor would almost certainly reject this structure. The protagonist must drive the plot. The protagonist must face the antagonist. The protagonist must be the one who achieves the goal. Bilbo does none of these things.

And yet The Hobbit works, and works brilliantly, precisely because it subverts those expectations. Bilbo’s arc isn’t about becoming a warrior or a dragon-slayer. It’s about becoming brave enough to leave his comfortable hole, clever enough to survive dangers he’s not equipped to fight, and wise enough to recognize that some conflicts can’t be solved with swords.

His greatest moment involves simply giving the Arkenstone to Bard and the Elvenking to use as a bargaining chip with Thorin, risking the dwarves’ friendship to prevent a war. In another way this would be rejected by modern publishing guidelines: his solution doesn’t even work. The moral is, Bilbo tried.

The Tonal Shift

For roughly three-quarters of the book, The Hobbit is a lighthearted children’s adventure. The narrator addresses the reader directly, makes jokes, and maintains a whimsical tone even during dangerous moments. Trolls argue about how to cook dwarves. Goblins sing silly songs. Bilbo’s primary concerns are missing meals and losing his pocket-handkerchiefs.

Then the Battle of the Five Armies begins, and the book transforms into something else entirely. The tone becomes somber, almost historical. The narrator pulls back from Bilbo’s perspective and describes the battle in broad strokes with armies clashing, leaders falling, the tide of war shifting. It reads less like a children’s story and more like a chronicle from The Silmarillion (though still a little easier to read).

Thorin’s death scene is tragic. His reconciliation with Bilbo, his acknowledgment that he valued gold over friendship, his admission that Bilbo’s courage and wisdom were worth more than any treasure. It’s a warning about how greed corrupts and works beautifully.

Connections to the Larger Mythology

The Hobbit was written before Tolkien had fully developed the mythology of The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings, but the revised edition and later writings wove it into the larger tapestry of Middle-earth.

The Necromancer whom Gandalf goes to fight in Mirkwood is Sauron, rebuilding his power in Dol Guldur. Gandalf’s absence during key moments of the quest is an indicator he’s dealing with a threat that will eventually lead to the War of the Ring. The White Council’s attack on Dol Guldur, mentioned briefly in The Hobbit, is detailed in the appendices of The Lord of the Rings and in Unfinished Tales.

The goblin and warg armies that attack during the Battle of the Five Armies may have been searching for more than just treasure. Sauron knew the One Ring was lost somewhere in the region. The goblins’ interest in the Lonely Mountain could have been driven by Sauron’s orders to search for the Ring, not just opportunistic greed. Tolkien never explicitly states this, but the timing is suspicious. Sauron is driven from Dol Guldur, and immediately afterward, a massive goblin army appears in the same region where Gollum lost the Ring decades earlier.

Thranduil, the Elvenking who imprisons the dwarves, is Legolas’ father. His cold treatment of Thorin’s company and his demand for a share of Smaug’s treasure add context to the tension between Legolas and Gimli in The Fellowship of the Ring. The distrust between elves and dwarves is rooted in specific historical grievances, including the events of The Hobbit.

Balin, one of Thorin’s company and a character who shows Bilbo particular kindness, later leads an expedition to reclaim Moria. His tomb is the one the Fellowship discovers in The Fellowship of the Ring, surrounded by the bodies of the dwarves who died trying to hold the ancient kingdom. That moment carries more weight when you remember Balin as a living character, not just a name on a tomb.

Goblins, Orcs, and Terminology

In The Hobbit, Tolkien uses “goblins” almost exclusively. In The Lord of the Rings, he uses “orcs.” These are the same creatures. Tolkien later explained that “orc” is the Elvish term and “goblin” is the Common Speech translation. He preferred “orc” because “goblin” had accumulated too many fairy-tale associations that didn’t fit his conception of the creatures.

The goblins in The Hobbit are more comedic than the orcs in The Lord of the Rings. They sing songs, they’re disorganized, and they’re more annoying than terrifying. This is partly due to the children’s book tone, but it also reflects Tolkien’s evolving conception of the creatures. By the time he wrote The Lord of the Rings, orcs had become darker, more disciplined, and more explicitly evil.

Other terminology shifts as well. The term “dwarves” instead of “dwarfs” was Tolkien’s invention, and he was quite proud of it. He also established “elves” as the proper plural rather than “elfs,” though that was already common usage.

Why It Endures

The Hobbit shouldn’t work by modern standards. The protagonist doesn’t defeat the antagonist. The tone shifts dramatically. The narrative perspective wanders. Key events happen off-page or without Bilbo’s involvement.

But it does work, and it endures, because Tolkien understood something that many modern writing guides miss: a story doesn’t have to follow a formula to be effective.

The tonal shift from children’s adventure to historical tragedy mirrors the journey itself. The quest starts as a lark, an adventure, a chance to see mountains and dragons. It ends with death, loss, and the recognition that some prices are too high. Bilbo returns home changed, wealthier but also wearier, and the Shire doesn’t quite fit him anymore. That’s the real cost of adventure, and Tolkien doesn’t shy away from it.

The prose is beautiful, even in the lighter sections. Tolkien’s descriptions of landscapes, his songs and poems, his ability to make even a hobbit-hole feel like a fully realized place, are all the marks of a master craftsman. The book is accessible to children while containing depths that reward adult readers.

Final Thoughts

The Hobbit earns a 9/10 and remains essential reading not just for Tolkien fans but for anyone interested in fantasy literature. It’s lighter than The Lord of the Rings, more accessible than The Silmarillion, and more narratively focused than Unfinished Tales. It’s also the foundation upon which everything else is built.

Reading it after The Silmarillion and Unfinished Tales adds layers of meaning. You recognize the significance of the Arkenstone as an echo of the Silmarils, a beautiful treasure that drives people to madness and war. You understand why Gandalf disappears to fight the Necromancer. You see the seeds of the War of the Ring being planted in the shadows of Mirkwood.

But The Hobbit also stands alone. You don’t need the larger mythology to appreciate Bilbo’s journey, Thorin’s tragedy, or the simple pleasure of a well-told adventure. It’s a children’s book that adults can love, a simple story with profound themes, and a structural experiment that succeeds despite breaking the rules.

What do you think? Should it be read before or after The Lord of the Rings and subsequent lore for maximum impact?

If you’re interested in a fun fantasy world, read The Adventures of Baron von Monocle six-book series and support Fandom Pulse!

"The Hobbit shouldn’t work by modern standards. The protagonist doesn’t defeat the antagonist."

I think he does, because the real antagonist is not Smaug. The dragon is a powerful agent of Morgoth and potentially a devastating weapon for Sauron. But the real enemy is pretty much what later Galadriel and Gandalf faced in LotR. They passed the test. And so did Bilbo.

Against all odds, Bilbo survived the adventure fit for the 1st Age of Middle-Earth, remained a hobbit and did not give into temptation, greed, ambition, pride and malice. His nature and faith in the simple life and eternal values outlasted all the evils thrown at him, even those slowly taking root among his friends, and he used all the simple goodness in him to drag back others from the precipice. He defeated a great antagonist indeed!

But it's true that in the current day and age, this would have been a much more up-hill battle with publishers than 90 years ago. Thankfully, Tolkien's publisher was wise enough to entrust his private review to his young son. Something that more publishers should do these days!

Incidentally, "elves" had a similar problem for Tolkien as "goblins". In the first versions of his mythos, Noldor Elves were called gnomes. And it actually was philologically correct!

THE HOBBIT is the perfect entry point into the grand spectacle of the world Tolkien created; written in a time when stories were not necessarily "dumbed down" for children--if today's generation can appreciate it, it is a perfect setup for the timeless themes of THE LORD OF THE RINGS-- much like Twain's TOM SAWYER draws the reader in to experience the later complexities of HUCKLEBERRY FINN...