The Dragonriders of Pern: How One of Science Fiction’s Most Beloved Sagas Faded from the Zeitgeist

The Dragonriders of Pern is one of the most beloved science fiction and fantasy properties ever created. Anne McCaffrey’s saga of telepathic dragons, their riders, and the fight against Thread captivated readers for decades, won Hugo and Nebula awards, and established McCaffrey as the first woman to win both honors for fiction. At its peak, Pern was a cultural phenomenon that attracted millions of readers and inspired fan communities that thrived long before the internet made fandom ubiquitous.

Today, Pern has largely disappeared from the cultural conversation. New readers discover Tolkien, Herbert, and Le Guin. They debate the merits of Sanderson, Martin, and Rothfuss. But Pern? It’s a footnote, a series older fans remember fondly but younger readers have never heard of. The franchise that once dominated bookstore shelves and convention panels has faded into obscurity, and understanding why requires examining the series’ history, its post-Anne McCaffrey evolution, and the media adaptations that never happened.

The Rise: Anne McCaffrey’s Vision

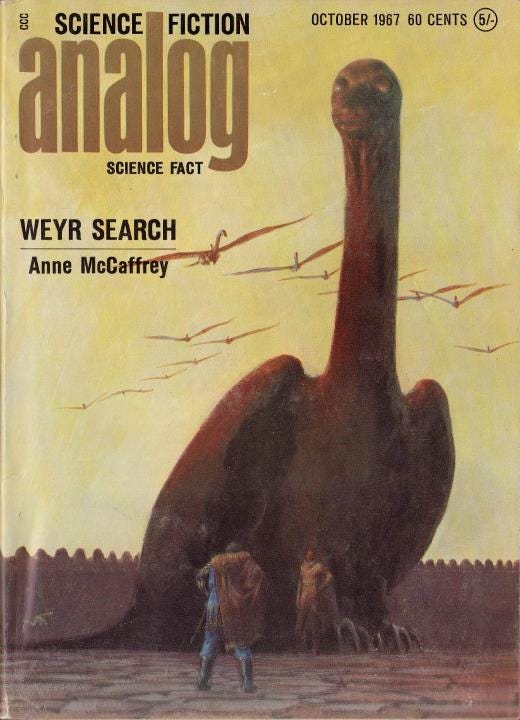

Anne McCaffrey published “Weyr Search” in the October 1967 issue of Analog Science Fiction and Fact, followed by “Dragonrider” in December 1967. These novellas introduced Pern, a lost Earth colony where genetically engineered dragons and their telepathically bonded riders defend against Thread, a deadly spore that falls from the sky in predictable cycles. The stories combined medieval social structures with science fiction underpinnings, creating a unique blend that appealed to both fantasy and SF readers.

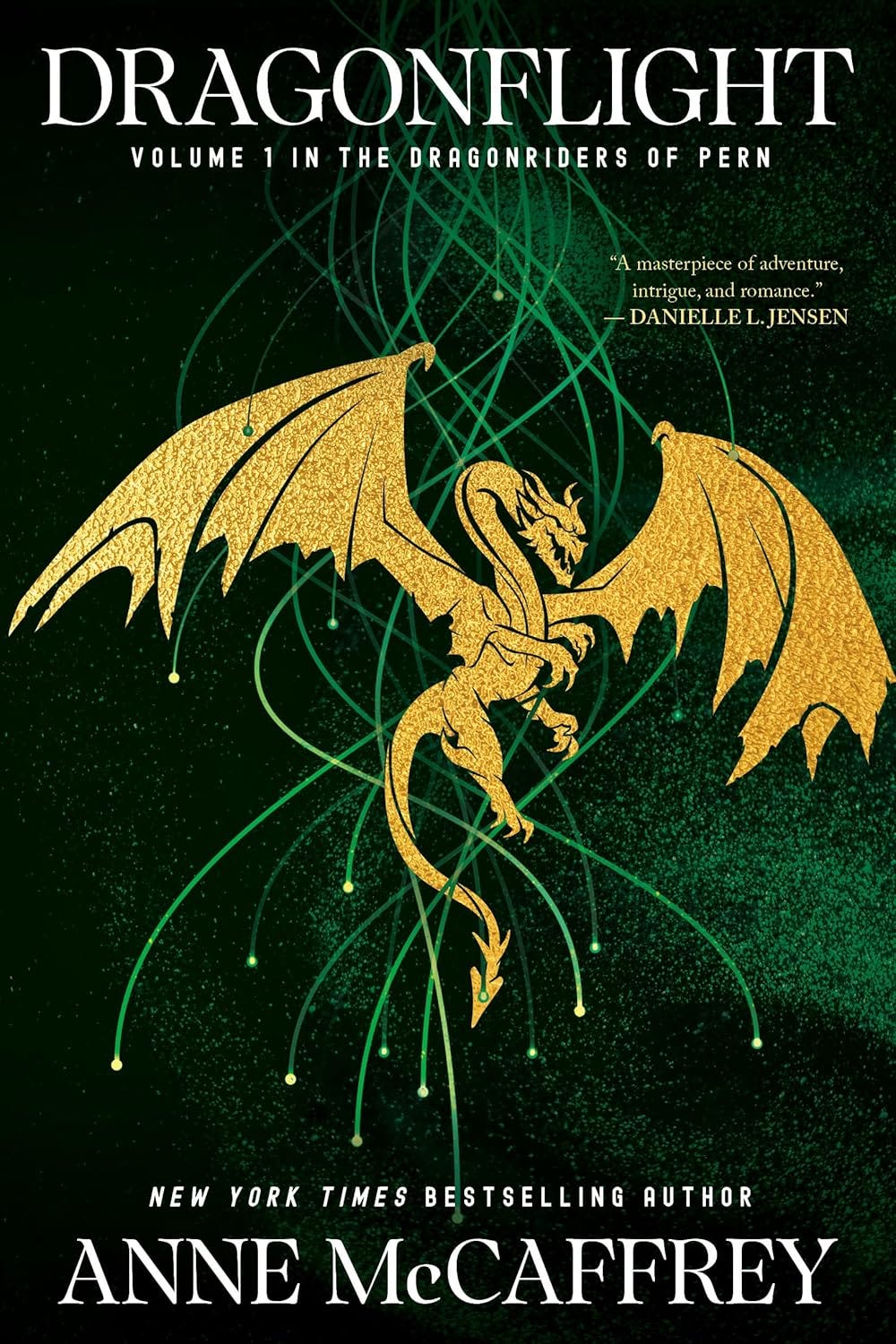

“Weyr Search” won the Hugo Award for Best Novella in 1968. “Dragonrider” won the Nebula for Best Novella in 1969. McCaffrey became the first woman to win either award, breaking barriers in a genre dominated by male authors. The two novellas were combined and expanded into Dragonflight (1968), the first Pern novel, which Locus subscribers would later rank ninth among all-time best fantasy novels.

McCaffrey built the series methodically. Dragonquest (1971) and The White Dragon (1978) completed the original trilogy, following Lessa, F’lar, and the dragonriders as they fought Thread and navigated political intrigue. The Harper Hall trilogy—Dragonsong (1976), Dragonsinger (1977), and Dragondrums (1979)—targeted younger readers while deepening the world’s cultural texture. These books introduced Menolly, a young woman who becomes a Harper despite her society’s restrictions, and they remain some of the most beloved entries in the series.

McCaffrey continued expanding Pern’s timeline, jumping backward and forward through history rather than progressing linearly. Moreta: Dragonlady of Pern (1983) and Nerilka’s Story (1986) explored the Sixth Pass. Dragonsdawn (1988) revealed Pern’s origins as a lost Earth colony, retconning the series’ science fiction foundations and explaining how dragons were genetically engineered from native fire-lizards. The Chronicles of Pern: First Fall (1993) collected short stories set during the early colonization.

By the 1990s, Pern was a multimedia franchise. The books sold millions of copies. Fans created elaborate Weyr-based role-playing communities online. McCaffrey licensed a collectible card game, a computer game (Dragonriders of Pern, 1983), and various other tie-ins. The series had staying power, and McCaffrey’s productivity kept it in the public eye.

The Decline: Todd McCaffrey and the Third Pass

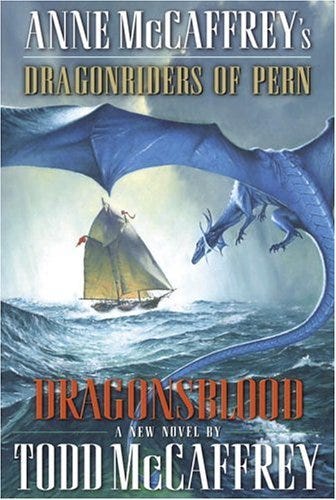

Anne McCaffrey’s health declined in the 2000s, and she brought her son Todd McCaffrey into the franchise as co-author and eventual successor. Dragon’s Kin (2003), co-written with Anne, introduced a new storyline set during the Second Interval. Todd continued with solo novels—Dragonsblood (2005), Dragonheart (2008), Dragongirl (2010)—focusing on the Third Pass, an era when Thread had been defeated and Pern was rediscovering lost technology.

Todd’s books were competent but divisive. He leaned heavily into the science fiction elements, exploring genetic engineering and another retcon of the watch whers. The prose was workmanlike, the pacing uneven, and the emotional resonance that made Anne’s books compelling was often missing.

Fan reception was mixed to negative. Longtime readers felt Todd’s books lacked the heart and character depth of Anne’s work. The Third Pass setting also removed the existential threat that had driven the original series since fans already know that the people there survived to another pass. The stakes felt lower, and the stories became more about political maneuvering and technological problem-solving than the life-or-death dragon-and-rider bond that defined Pern.

Sales reflected this. Todd’s books sold respectably but never matched Anne’s peak numbers. The fanbase fragmented, with some readers embracing the new direction and others abandoning the series entirely. When Anne McCaffrey died in 2011, Todd continued writing Pern novels, but the momentum was gone.

Todd’s final solo Pern novel, Sky Dragons (2012), marked the end of his active involvement in the series. He co-wrote Dragon’s Time (2011) with Anne before her death, but after Sky Dragons, the publishing schedule slowed dramatically.

Gigi McCaffrey and the Quiet End

In 2018, Anne’s daughter Gigi McCaffrey published Dragon’s Code,. The book was set during the Ninth Pass, returning to the era of Anne’s most popular novels. It was intended as a revival, a return to the classic Pern feel that fans had been missing.

It didn’t work. Dragon’s Code received little marketing, minimal media attention, and poor sales. Most Pern fans didn’t even know it existed. The book came and went without making an impact, and no further Pern novels have been announced since.

The McCaffrey estate has been quiet about the franchise’s future. There are no new books in development, no announcements of reprints or special editions, and no indication that Pern will continue as an active literary property. The series that once produced multiple books per year has been dormant for seven years.

The Real Problem: No Media Adaptations

The biggest reason Pern faded from the zeitgeist is simple: it never got a successful screen adaptation. In the modern era, genre franchises live or die based on their presence in film and television. The Lord of the Rings became a cultural juggernaut because of Peter Jackson’s films. Game of Thrones revived interest in George R.R. Martin’s books. The Expanse, Foundation, and even lesser-known properties like The Magicians found new audiences through TV adaptations.

Pern never got that boost. Despite decades of attempts, no Pern film or series has ever been produced.

The closest was Ronald D. Moore’s 2001-2002 pilot for the WB Network. Moore, fresh off his success relaunching Battlestar Galactica, developed a Pern series with sets built, cast chosen, and a completed pilot script. The project was ready to shoot. Then WB executives demanded changes—they wanted the show to be more like Buffy the Vampire Slayer or Xena: Warrior Princess, with quippy dialogue, campy tone, and a younger, more “accessible” cast.

Moore refused. He later said he had no regrets, because he’d rather see Pern unadapted than badly adapted. The pilot was shelved, the sets were dismantled, and Pern’s best chance at screen success died.

There have been other attempts. In 2018, Warner Bros. announced they were developing a Pern film, but nothing came of it. Various producers and studios have optioned the rights over the years, but none have made it past the development stage.

The problem is that Pern is expensive to adapt. Dragons are CGI-intensive, and the series requires large casts, multiple locations, and extensive worldbuilding. Studios are reluctant to invest that kind of money in a property that doesn’t have the name recognition of Tolkien or Martin. Pern is beloved by its fans, but it’s not a household name, and that makes it a risky investment.

The lack of adaptation created a vicious cycle. Without a film or TV series to introduce new readers, the books stopped reaching younger audiences. Without new readers, publishers lost interest in reprinting backlist titles or commissioning new entries. Without active publishing support, the series faded from bookstore shelves. And without visibility in bookstores, even fewer people discovered Pern.

Why Pern Mattered

At its best, Pern was groundbreaking. McCaffrey created a world where women were dragonriders, leaders, and heroes at a time when most fantasy relegated female characters to supporting roles. She blended science fiction and fantasy in ways that felt organic rather than gimmicky. She built a universe with deep history, complex politics, and a lived-in feel that made readers want to stay.

The dragon-rider bond was the emotional core of the series. The telepathic connection between dragon and rider, the Impression ceremony where young candidates bonded with newly hatched dragons, and the idea that losing your dragon meant losing part of yourself—these were powerful, resonant concepts that gave the series its heart.

Pern also pioneered online fandom. In the early days of the internet, Pern fans created elaborate role-playing communities where they could Impress their own dragons, join Weyrs, and live out stories in McCaffrey’s world. These communities predated modern fandom platforms and helped establish the template for how fans engage with fictional universes online.

Can Pern Come Back?

Pern’s fade from the zeitgeist isn’t permanent. The books are still in print, and the core series remains excellent. If a studio finally produced a quality adaptation, the franchise could experience a renaissance.

But that requires someone willing to invest in the property. It requires a creative team that understands what made Pern special—the dragon-rider bond, the existential threat of Thread, the blend of medieval society and science fiction underpinnings. It requires a studio willing to spend the money on CGI dragons and large-scale production without demanding the story be dumbed down or modernized into unrecognizability.

Until that happens, Pern will remain what it is now: a beloved series that older fans remember fondly, that younger readers have never heard of, and that the culture has largely forgotten. It’s a tragedy, because Pern deserves better. Anne McCaffrey created something special, and it’s a shame that the series she built has faded so completely from the conversation.

Maybe one day, someone will give Pern the adaptation it deserves. Until then, the dragons sleep, and the world has moved on.

What do you think? Have you read Pern, or is it a series you’ve heard of but never explored? Should someone take another shot at adapting it for screen?

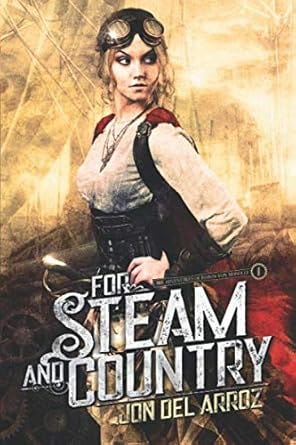

If you’re interested in a fun fantasy world, read The Adventures of Baron von Monocle six-book series and support Fandom Pulse!

“The biggest reason Pern faded from the zeitgeist is simple: never got a successful screen adaptation.“

Additional information - That is incorrect. Most of the top classic science fiction works still sell despite being ignored by publishers (all those male authors!) and never scored with Hollywood. Even the Gor novels, banned by publishers, condemned by the Great and Wise, still sell in ebooks.

Alternative perspective - The dragonrider books were popular as the breakthrough novels in the Girls Are Great subgenre of SF. Now SF is a subgenre of Girls Are Great. Every other new book features omnicompetent beloved Mary Sue’s. SF in TV and films, ditto.

It’s like reading Tarzan or John Carter on Mars, breakthrough novels - but now their tropes have been run to exhaustion.

Starfleet Academy tries to resuscitate the G Are G genre through exceptional weirdness. Time will tell if that works.

I read several of the novels back in the day (the first two or three Draongriders, the three Harperhall, and a couple others, all before McCaffrey died), I remember them as pretty good. Also realized early on that Pern couldn't be done then, certainly not in live-action (the Dragonslayer film around that time was amazing, but that only had one dragon, and not for very much screen time).

Given the currents in SF/F since then, I wouldn't trust any established name to adapt the stories without forcing "modern" sentiments into the fore. And even without that bias, a lot of the "meat" fo the stories was internal - thought and emotion. That kind of story needs a very skilled writer and director. And just making a film about Thread-fighting would probably end up as just another SFX-fest - maybe a very cool one, but still, with the fatigue around Marvel/DC and Star Wars/Trek, I doubt there's enough draw to justify.

Growing AI film capability might change some of that equation, though...